Why police want your smartphone data

It's time to push back against the harvesting of smartphone data by police, border agents and government organizations. Here's why.

A tension has existed for centuries between the desire for efficient law enforcement on the one hand and the desire for personal privacy on the other.

That’s why the framers of the constitution added the 4th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees the right for Americans’ “persons, houses, papers, and effects” to be free from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” The Amendment does allow searches, but only after “probable cause” has been established. When they search for something, they have to specify what they’re looking for.

In other words: The Constitution bans police fishing expeditions that just go looking for a crime, any crime.

Unfortunately, they didn’t mention smartphones.

We all want criminals to be caught. But we don’t want to live in a sci-fi dystopia where computers sift through all human data day and night fishing for crimes and, for example, using the data from one person to expose the crimes of another — say, a family member or friend.

The reality is that the balance between law enforcement’s instinct to gather all the data that’s out there and the public’s desire to keep personal data private is upset with each new generation of technology. Every time there’s a new capability, police try to use that capability to tilt the game in their favor.

The biggest disruptor is the smartphone — the ultimate tracking, data gathering, personal information-exposing technology ever invented. Because of that, police really, really want it.

The Justice Department’s efforts to catch former US president Donald “Teflon Don” Trump — who is infamous for getting others to commit crimes on his behalf without himself being implicated — have turned to what they hope are rich nuggets of gold in the smartphones of nine Trump associates.

The feds this week seized the phones of Rudy Giuliani, Jeffrey Clark, John Eastman, Victoria Toensing, Michael McDonald, Scott Perry, Boris Epshteyn, Mike Roman and last and definitely least, Mike Lindell, the My Pillow guy. They’re hunting for evidence in Trump’s larger scheme to steal the 2020 election.

Meanwhile, Australian “technology detection dogs” are in the news. Australian Federal Police held a “Technology Detection Dog Symposium” recently to further the cause of developing a nationwide pack of dogs that can use their keen sense of smell to find smartphones and other data-storing personal devices like so many truffles.

The problem this solves for police is that when searching a home for evidence, they might miss hidden hard drives and flash drives and thumb drives containing compromising material. The idea is that if there’s any data-storing device in the house, car or place of business they’re searching, they want to find it and use it in their investigations. That’s how valuable electronic data is.

All this news points to police going to extreme lengths to make sure they get the smartphone data pertinent to alleged crimes. But what about the smartphone data of people not even accused?

Before the pandemic, I warned you about changing rules around airport security agents and their legal right to download your personal and business data.

We learned today that as many as 10,000 electronic devices (mostly smartphones) now have their contents copied at border crossings (mostly airports) each year (and growing). This data is fed into a giant database that’s part of the Department of Homeland Security’s Automated Targeting System and kept there for up to 15 years. The data in that database is currently accessible by some 2,700 border patrol officers without a warrant, and most of the victims aren’t charged or even suspected of a crime.

(Here’s my advice for how to protect your data from such invasive searches.)

This kind of data collection — affected at scale and dropped into a long-term database that can be accessed later — is by far the most insidious and threatening scenario, and I’ll tell you why.

Smartphones have many attributes that make them perfect criminal data gathering and storing devices. They track and store location. They contain message histories and phone logs. They contain documents and photographs. They can tell cops who met with whom, when, where and what they talked about.

This raises the other factor with cell phones that make them such juicy targets in criminal investigations — messaging involves multiple parties. So if one party deletes their messages, another party may not have, and the second party will have all the texts from the first party. That knowledge forces all parties to fess up and admit conversations they had, whether they deleted them or not.

But the biggest attribute is that once smartphone data is collected, officials can apply increasingly sophisticated AI analysis to find connections that expose law-breaking and other compromising material not only by people who own the smartphones, but by other people in their contact lists, text messaging logs and email histories.

Smartphone data is the ultimate pond for (what should be un-constitutional) fishing expeditions to find crimes.

If you compile a big enough database of smartphone data and point sufficiently advanced AI at that database, you can essentially instruct the AI to list all the crimes with associated criminals, and the AI can provide this list in seconds. AI can find patterns and details that humans would miss.

They can triangulate data from multiple people, meaning that a photo from your phone, a text message from another phone and a GPS history from a third phone can in concert implicate your nephew in a crime, providing incontrovertible proof and making you an unwilling and unknowing “witness” against your own family member.

This is not the world most of us want to live in. We need a new public awareness about the risks and pitfalls of smartphone data harvesting, collection, retention and AI processing by law enforcement organizations. And we need to advocate the inclusion of smartphones into the list of Constitutionally protected personal spaces to go along with “persons, houses, papers, and effects,” because it obviously belongs on that list.

Mike’s List of Brilliantly Bad Ideas

1. Has keyboard enthusiasm gone too far?

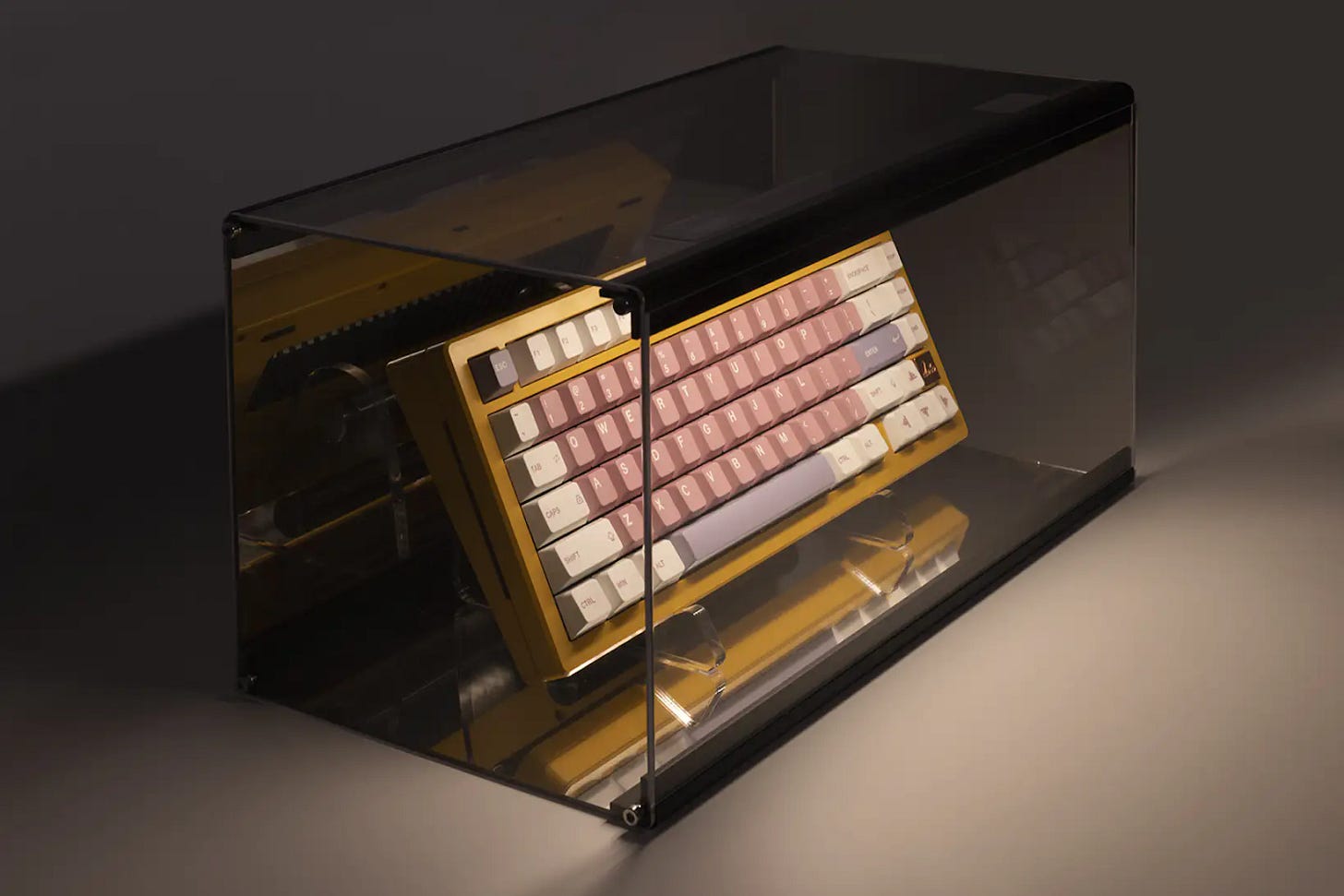

Keebmonkey is now selling a product called the Wireless Keyboard Display Box. It’s a translucent case for displaying your keyboard like it’s the fricken Hope Diamond at the Smithsonian. Reflective interior surfaces let you see the keyboard from multiple angles. And a motion-detector triggers a light, so that when anyone walks up to the case, the keyboard is illuminated.

2. Has LEGO enthusiasm gone too far?

The Pixel is a LEGO-compatible keyboard from MelGeek. It’s a regular keyboard, but with LEGO-compatible studs for adding LEGO bricks, Minifigs and other LEGO parts. Better still each key is actually a cap on top of a LEGO-compatible key, so you can remove the cap and add LEGO bricks as keys you type on.

3. VR goggles for your mouth. Why, Japan? Why?

A company called Shiftall (read it carefully — it’s not “Shitfall) is hawking a product called the Mutalk. It looks like VR goggles for your mouth. The purpose of the product is to be able to trash-talk other avatars in virtual reality without upsetting the librarian or waking up your mother from the basement. It lets you talk into a microphone without being heard by others nearby, and also to shield your voice from ambient sound. I don’t know what the “metaverse” will look like, but this is what YOU will look like in the metaverse.

Mike’s List of Shameless Self Promotions

It's time to quit quitting on the quiet quitters

CISA certification: what you need to know

Why Apple is building two different smartglasses platforms

Get ready for the rise of imposter employees