Are you suffering from AI-induced creative paralysis?

Why make anything when AI can make it better, faster and cheaper?

The lightning-fast pace of AI progress is… depressing. Wait, what?

The new malady of the moment is something I call “AI-induced creative paralysis.”

Here’s the problem: Generative AI tools like ChatGPT emerged suddenly and improved rapidly. Sure, the chatbots hallucinate and the AI image generators can’t count human fingers. But any thoughtful person can conclude that it’s only a matter of years or months before AI performs perfectly.

Once this conclusion is reached, content creators, actors, entrepreneurs and developers are asking themselves: What’s the point?

Why should a student study photography when before graduation, genAI tools will be able to produce perfect pictures on any subject in seconds?

Why should a writer start a two-year book project when in two years any random schmuck can produce better books on the same subject at the rate of 10 books a day?

Why should a high school student learn to code, when AI will instantly produce better code?

Why should an entrepreneur launch a non-AI tech product, when every dollar of venture capital is going to AI startups?

For that matter, why build any kind of informational website, when Google will just hoover it up with everything else online and present your information un-attributed in their AI-generated search responses?

You probably heard about the recent OpenAI scandal whereby the company approached actress Scarlett Johansson to provide the voice for its GPT-4o assistant.

(Johansson voice-acted for the AI agent in the movie “Her,” with which actor Joaquin Phoenix’s character becomes obsessed. Turns out OpenAI CEO Sam Altman is a real-life Joaquin Phoenix, similarly obsessed.)

The conventional wisdom is that after Johansson turned OpenAI down, they created a ScarJo-like voice for the assistant anyway. They claimed it wasn’t based on the actress’s voice (an obvious lie), then terminated the voice when Johansson complained.

But reasonable speculation (by Edward Zitron under the headline, “Sam Altman Is Full Of Shit”) suggests the reverse is true — that “OpenAI simply pirated her likeness and then tried to bring her onboard in a failed attempt to eliminate any potential legal risk.”

In other words, if this take is right, OpenAI’s instinct was to just create Scarlett Johansson’s voice using AI. Involving the actual person of Scarlett Johansson was a mere afterthought and legal fig leaf.

Voice actors in the short run and actor actors in the long run might fear: Why would the world need actors when a perfect puppet can be created in a computer?

This is what last year’s Writers Guild of America strike was about, in part. In addition to payment and staffing demands, the Writers Guild demanded safeguards to ensure that AI would not encroach on writers' credits and compensation.

After all, it’s only a matter of time before AI can not only perfectly recreate Scarlett Johansson’s voice, but also her face, body, gait and acting style. While Scarlett Johansson ages like any other human, the AI Scarlett Johansson can be any age for any movie and keep making movies until the end of time. And while the real ScarJo is one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood, the AI version is cheap.

Ergo: “AI-induced creative paralysis.”

My advice to creatives: Keep creating

The belief that one’s own creative profession will be steamrolled by better/faster/cheaper AI tools is an assumption — sort of. That it will be faster and cheaper is certain. But “better” is in the eye of the beholder.

What’s also certain is that a range of backlashes are coming. Legal backlashes. Technology and business backlashes. And backlashes in the court of public opinion.

Whenever new creative technology emerges, both the public and the creative industry responds in unpredictable ways. One great example of this phenomenon happened in France during the 19th Century. In the year 1800, artists painted pictures for artistic expression, sure, but mainly for the utilitarian capturing of images for marketing, memory, propaganda and religious inspiration. By 1900, photography handled most utilitarian image capturing. So where did the painters go?

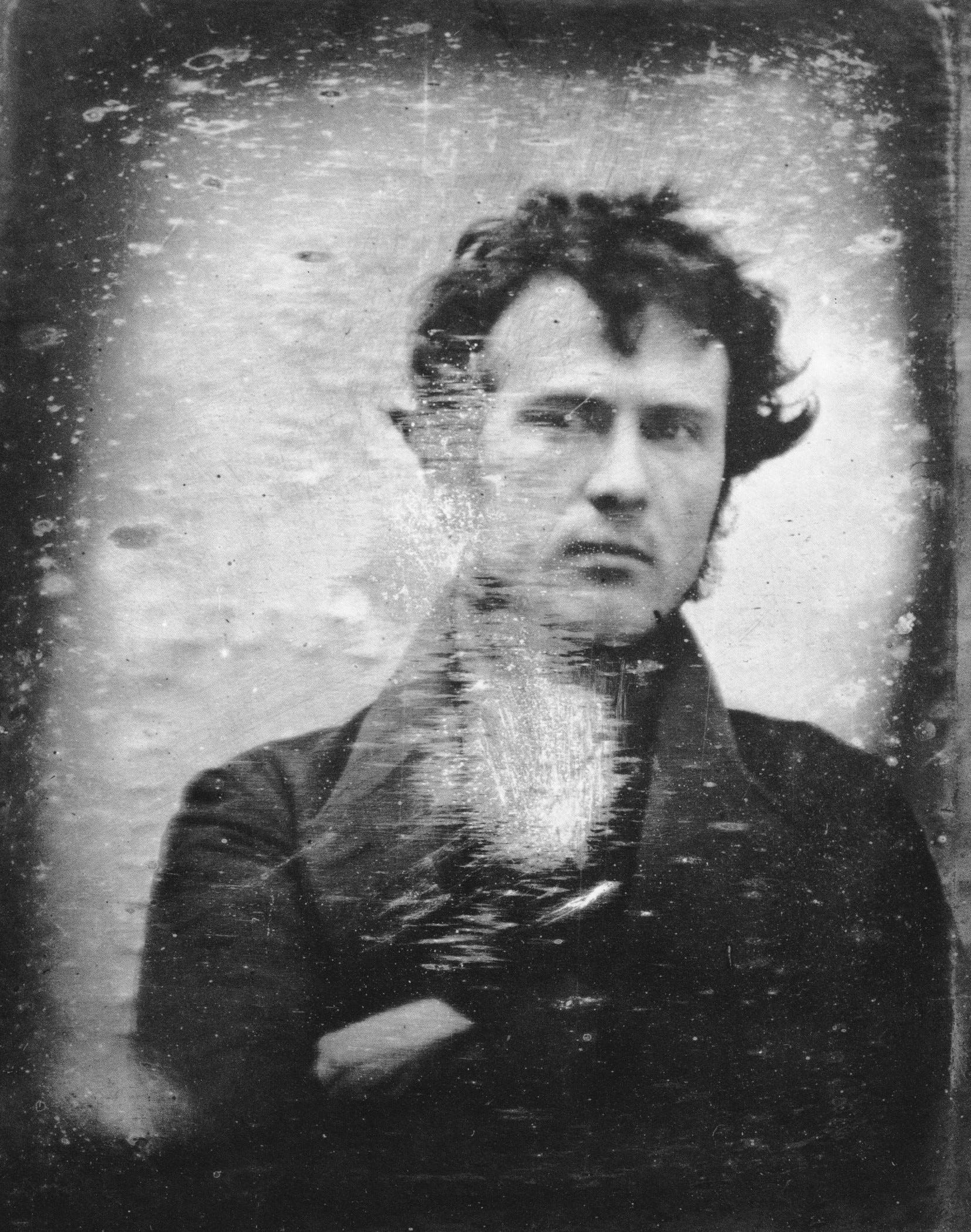

In 1839, French artist, photographer, and physicist Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre invented the daguerreotype photography process, which produced highly detailed images on silver-plated copper sheets, which popularized and democratized photography. (It was also that year when American Robert Cornelius took the world’s first selfie — pictured up top — which he made using a daguerreotype camera).

Instead of sitting for hours for a painted portrait, people could now sit for a few minutes for a “better” photograph. Landscapes, still-lifes and other scenes were rendered far more efficiently with cameras.

What was a painter to do?

In the 1860s, French artists studying under the Swiss artist Charles Gleyre — you know their names: Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley and Frédéric Bazille — invented the impressionist style. They did with paint what cameras could not do with film.

Shameless Self-Promotion

AI glasses + multimodal AI = a massive new industry

A glimpse at the powerful future of information

Why you’ll soon have a digital clone of your own

Grey Matter podcast: A cosmopolitan bon vivant on being a Gastronomad (and AI)

Inside AI podcast: Google Gemini and the Wall of Noise

Check out all Elgan Media content!

My Location: Venice, Italy

(Why Mike is always traveling.)

I'd welcome AI contributions in warning society about malignant narcissists, sociopaths & psychopaths, because CNI has unlimited creative angles that are only restrained by time and resources. However, since most humans miss a lot of the abstraction & nuance of the psychology, I don't expect anything very helpful, accurate or useful out of AI for quite a while.