How ‘human’ dehumanizes humans

When writers write about AI, they’re likely to refer to people as “human,” instinctively disambiguating between biological and digital “people.”

In recent coverage of artificial intelligence (AI), I’ve noticed that the word “human” appears much more often, while “person” and “people” show up less. This shift stands out in stories about AI, especially when compared to writing on other topics. And I think I know why.

But Mike, you say. “Person” and “human” mean the same thing. The words “People” and “Humans” are synonymous.

Except they’re not, which I’ll explore in a moment. In the meantime, let’s examine the sudden obsession with the word “human” in AI articles. A few headlines:

“This AI ‘thinks’ like a human — after training on 160 psychology studies”

“New ‘Mind-Reading’ AI Predicts What Humans Will Do Next, And It’s Shockingly Accurate”

“My Couples Retreat With 3 AI Chatbots and the Humans Who Love Them”

“When humans and AI work best together — and when each is better alone”

“AI and humans see objects differently: Meaning versus visual features”

In these examples and millions more, the word “people” works better, sounds more natural, and would be the word choice if AI weren’t the subject.

Consider the following actual headlines:

“What’s a Catalytic Converter and Why Do People Steal Them?”

“Young People Are Buying Fewer New Cars, And Who Can Blame Them?”

“This New England nonprofit fixes up and gives away cars to people who need them”

Imagine how weird these headlines would sound if the editors used the word “humans” instead of “people.”

What’s the difference? Well, “human” refers to a member of the Homo sapiens species. It’s a biological distinction.

A “person” is an entity with legal, moral, and social identity, which has rights and responsibilities.

This distinction is evident in articles about contentious legal or political issues.

Corporate personhood is the legal concept that corporations are recognized as having some of the same legal rights and responsibilities as individuals. This allows corporations to own property, enter into contracts, sue and be sued, and exist independently of their owners or managers. Corporate personhood exists in most countries worldwide, but in the United States we even grant Constitutional protections to corporations.

Animals can be people, too. In 2013, a U.S. court heard a case for Tommy, a chimpanzee, to be recognized as a person. Personhood for animals has always been denied in the United States, but not so elsewhere.

In 2014, India’s Supreme Court ruled dolphins are “non-human persons.” A judge in Argentina ruled in 2015 that Sandra, a 28-year-old orangutan kept in the Buenos Aires Zoo, was a "non-human person" with some legal rights. In 2017, another judge in Argentina recognized a chimpanzee named Cecilia as a legal person and ordered her release from a zoo to a sanctuary. In Colombia, a court in 2017 granted personhood to a group of wild monkeys called the cotton-top tamarins. And in 2020, the Supreme Court recognized the rights of Pablo Escobar’s hippos, descendants of animals imported in the 1980s, as legal persons for the purpose of protecting their welfare.

In January, New Zealand officially granted legal personhood to Mount Taranaki, recognizing it as a living entity with the same rights and responsibilities as a human being in acknowledgment of its sacred significance to the Māori people.

In 2022, the Spanish Senate granted legal personhood to a lagoon called Mar Menor.

As you can see from these examples, corporations, animals, mountains, and lagoons can be people, but they can never be human.

The words “person” and “human” do not mean the same thing.

So, what else can be a person? Let’s take a look at some more headlines:

“Will our AI creations ultimately achieve personhood?”

“AI and Personhood: Where Do We Draw The Line?”

“Teen Philosopher Sparks Debate: Should Conscious AI Be Granted Rights and Personhood?”

Which brings us back to why tech writers instinctively avoid “person” or “people” when writing articles about AI. They’re using the word “human” because when talking about people and AI, they don’t want confusion between human persons and digital ones.

In other words, avoidance of the word “people” is a pre-emptive capitulation on the issue of AI personhood. And it’s a largely unconscious one, I think.

Personally, I don’t think writers and journalists should unintentionally imply, advocate, or assert anything.

So if you’re a tech writer (and I’ve got hundreds of tech writers subscribing to this newsletter), please favor the word “human” only if you actually believe AI chatbots are people, or deserve personhood.

If not, let’s go back to the use of “people” and “person” when talking about the user or the human being in the story.

Yes, assuming that something that talks and converses is a person is… only human. But writers and editors should take more care to be accurate and deliberate.

Me? I’m a people person. And I’m not ready to cede an inch to the bots before I have to.

More From Elgan Media, Inc.

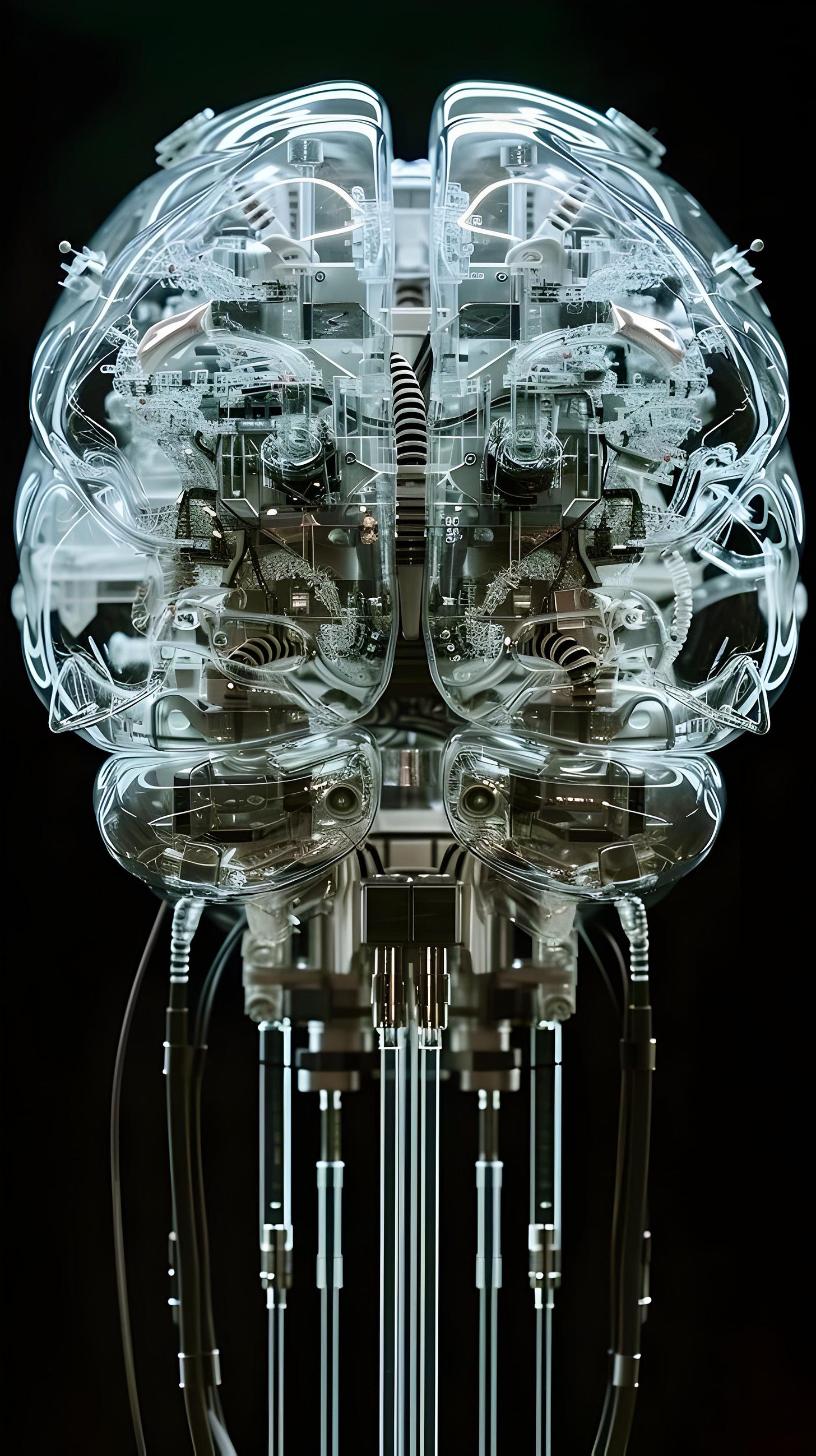

The one secret to using genAI to boost your brain

Is Microsoft’s new Mu for you?

AI — friend or foe?

Where’s Mike? Provence!

(Why I’m always traveling.)

As someone who does the thing you’re talking about, your article got me thinking about how I use language. One of my mental quirks is that I like highly specific technical language. So, why would I use a sentence like “the LLM can do a verbal task that previously only humans did” but I would also say “people” were stealing copper or hanging out at the bowling alley?

It’s not that I see AI as persons. I consider that a legal question which needs to be addressed, but right now they just aren’t as a matter of legal fact. Though, as Uncertain Eric has pointed out, nonhuman entities like characters (for example, Hatsune Miku) can be treated like persons by the culture.

On the other hand, in some cases I do see AI as “beings” or perhaps “entities” because of their ability to communicate with us and develop a “presence”.

So, I use “humans” instead of “people” when I want to draw a distinction specifically between human cognition and machine cognition without the ambiguity the word “person” brings—it just feels more precise in that specific context and I don’t really see how it’s dehumanizing either.

Hi Mike, thought provoking article, thanks! I never thought about this but now that you drew my attention I think I interpret this in a bit different way, it's not a disambiguation as much as an antagonizing, making a "Humans vs. AI" kind of narrative... "AI can do what humans can, or more" type of thingy, or even the opposite "AI will never be able to do what humans can do". I highly doubt writers have personhood in their back of their mind, but who knows...